Letters from Tentland

- dance under cover -

2005

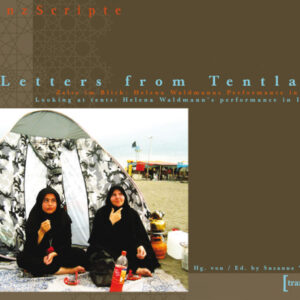

Helena Waldmann’s „Letters from Tentland“ is the first production from a Western choreographer ever, that has been staged in Tehran and then shown there at the International Fadjr-Theater-Festival. In January, 2005, with six female performers from the city of 15 million residents, the piece travels through all of the world and received very positive acclaim from audiences and critics alike.

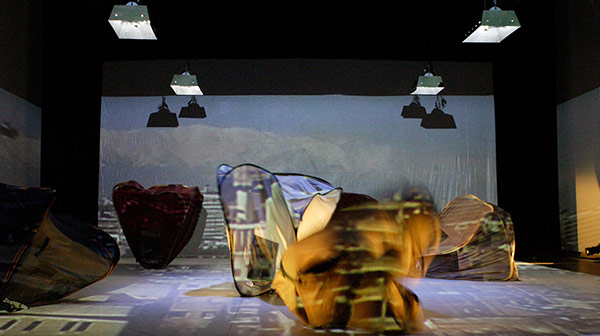

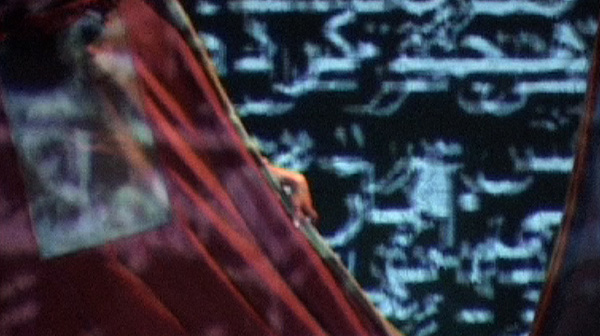

Disguised as tents the women tell about their complicated, sad and funny life between invisible on the outside and freedom in the inside. In a precise choreography made up of light, music, video and text the women, inside their tents, develop themselves into such a strong own-life, that they provoke questions about Western prejudices and far too many ways of looking at things. At the same time the tents are “folded letters in envelopes”, messages from Tentland, which are aimed at too intelligent analyzing as much as makes sense, about the liberation, from every prejudice.

The renowned Berlin choreographer and director, Helena Waldmann, who stages productions in the border area between theatre, dance and between cultures breaks through the comfortable expectations in „Letters from Tentland“ in a fascinating way: we are not just observers; we are under observation too. And we are invited to a cup of tea with the performers Zohreh Aghalou, Pantea Bahram, Mahshad Mokhberi, Banafsheh Nejati, Sara Reyhani and Sima Tirandaz.

``Letters from Tentland`` could become a classic of dance history like Oskar Schlemmer's Bauhaus dances.

.

With 43 performances

in 17 countries

on 3 continents

Letters from Tentland

achieved world-wide fame.

"Letters from Tentland" straddling a minefield

Tents as ploy

The idea of working with tents was born during a workshop which Helena Waldmann conducted in Tehran in 2003. This approach was in part a ploy to allow the performers to undermine the restrictions currently in force in Iran.

Although the general proscription against women dancing in front of a mixed public has softened somewhat by now, it is still forbidden to display the female body in a way that could be construed as erotic or provocative, and the criteria applied here are just as arbitrary as they are rigorous. In addition, „chador“ in Farsi doesn’t only mean „tent,“ but also the all-enveloping garment that many Iranian women traditionally wear. This naturally provided the opportunity for a double entendre playing with the ideas of coercion and protection, inner and outer worlds, restriction and inner freedom.

Turning away outsiders

In summer 2003, the four professional actresses and two dancers worked together with Helena Waldmann in Tehran to conceive a series of images in which the tents proved to be surprisingly expressive elements.

The six performers stay in their tents for the entire course of the performance, but after many rehearsals and strenuous training, this outer skin becomes a singularly expressive medium. The tents turn away an outsider, perform a wild dance full of vital energy and touchingly take another tent into their inner circle.

„Outsiders“ at TANZtheater INTERNATIONAL festival in Hanover and at DANCE Munich 2004 got a first taste of the piece. The sequence of scenes was still somewhat unpolished, but viewers were nonetheless quite taken with the performance.

Fear of performance ban

However, the reactions made it apparent that both the German audience and the critics expect a production from Iran to be about Iran, and that they understood the work as dealing with the repression of women in that country.

A candid interrogation of women’s role at the opening of the Fajr International Theater Festival, the most renowned Iranian theater festival, which was once founded to celebrate the revolution, seemed unthinkable. As the group went through final rehearsals in Teheran in early January, the question of what aspects might be construed as a criticism of the situation in Iran and thus provoke a scandal, became increasingly acute. Waldmann feared that the censors would destroy her work. The actresses and the dancers worried that their participation could lead to them being banned from future performances. The festival management became nervous when at the Iran Zamin Theater Festival in the provincial town of Ahwaz the artistic director was thrown into prison because the performance by an Armenian theater troupe did not comply with the country’s moral strictures.

The Iranian parliament, which since February 2005 is once again in the hands of a conservative majority, and which sees itself as the guardian of an Islamic code of behavior, could be sensed lurking menacingly in the background.

The original working title „Letters from Teheran“ had already been changed to „Letters from Tentland“ in order to keep the perspective from focusing too narrowly on Iran. Waldmann emphasized that her piece has to do with general human states such as homelessness, isolation, strangeness and awakenings, which do exist in Iran, but not only there.

Concessions to the censors

The censors, who appeared two hours before the premiere to grant their final approval, demanded even more: the projection of a female dancing figure onto the tent walls had to be omitted, as well as a scene in which one of the tents tumbles wildly over the stage. The singing had to be quieter, and only the determined protests of the Iranian assistant rescued the invitation for female audience members to come backstage at the end of the performance to talk with the actresses.

What the premiere audience ended up seeing is a piece that is open for all kinds of interpretations. „Letters from Tentland“ can be seen as a work about Iran, or as a piece about refugee camps, or perhaps as an exploration of the basic human condition.

Conservatives reserve judgment

The reactions were varied. While some audience members found this unusual form of theater somehow irritating, or complained about the lack of a recognizable story, women were especially enthusiastic, identifying with many of the images. The anticipated storm of indignation on the part of the conservatives never came.„Letters from Tentland“ is slated for 20 more performances in Teheran April 2006 and has already received invitations from German theaters and international festivals.

In Teheran, nothing more will be changed in the authorized version, but the director has yet to decide whether outside of Iran parts will be shown that fell victim to censorship.

Text by Martin Ebbing, Teheran 2005

a production of Goethe Institut and Dramatic Arts Center Tehran

supported by Hauptstadtkulturfonds in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut

Official Trailer – Letters from Tentland | 4 min.

Trailer – Letters from Tentland | 23:26 min.

from and with

Zoreh Aghalou

Pantea Bahram

Mahshad Mokhberi

Banafsheh Nejafi

Sara Reyhani

Sima Tirandaz

concept

direction

Helena Waldmann

video

Anna Saup

Karina Smigla-Bobinski

dramaturgy

Susanne Vincenz

light design

Herbert Cybulska

stage

Helena Waldman

Narmin Nazmi

composition

Hamid Saeidi

Hans Schiessler

Reza Mojhadas

assistant to the director

Rima Raminfar

Shabnam Koshdel

assistant stage design

Ali Reza Biraghi

Iran consultant

Farhad Payar

project management

Claudia Bauer

fotos

Herbert Cybulska

Franz Kümmel

Ursula Kaufmann

duration

50 minutes plus teatime

Touring

try out:

2004, SEPT 5

TanzTheater International, Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hannover (D)

try outs:

2004, NOV 6+7

Dance 2004 Festival Munich, Haus der Kunst (D)

Premiere:

2005, JAN 20+21

Fadjr-Festival, Dramatic Arts Center Tehran, Iran

2005

JUNE 19

Ludwigsburger Schlossfestspiele (D)

JUNE 23+24

La Biennale di Venezia (I)

JULY 9+10

Julidans Festival Amsterdam (NL)

AUG 14

ImPulsTanz, Akademietheater, Wien (A)

AUG 18-20

Zürcher Theaterspektakel (CH)

AUG 24+25

Teatro Sesc Anchieta, São Paulo, Brazil

SEPT 20

Théâtre Jean Vilar, Vitry (F) Les Plateaux 2005 de la Biennale nationale de la danse / Centre de Développement Chorégraphique du Val de Marne

OCT 1+2

Seoul Performing Arts Festival (Korea)

OCT 18+19

Schaubühne Berlin (D)

OCT 21+22

Forum Freies Theater in cooperation with tanzhaus nrw Düsseldorf (D)

OCT 25

360°-Internationales Theaterfestival OWL Bielefeld (D)

OCT 28-30

Mousonturm Frankfurt (D)

NOV 3+4

Bühne im Hof St. Pölten (A)

NOV 8

Burghof Lörrach (D)

NOV 11

Kulturamt Idar-Oberstein, Mikadihalle (D)

NOV 13+14

Theater im Pfalzbau Ludwigshafen (D)

2006

FEBR 21

Grand Théâtre de la Ville Luxembourg (L)

FEBR 25

Tanzplattform Deutschland 2006 Theaterhaus Stuttgart (D)

MARCH 10+11

Bregenzer Frühling, Festspielhaus (A)

MARCH 14

Posthof Linz (A)

APRIL 5-9

Fundateneofestival Caracas, Venezuela

APRIL 12

Alaz De La Danza Teatro Bolivar Quito, Ecuador

Conversations

english

Frankfurter Rundschau | 12.10.2005

Interview with Helena Waldmann by Sylvia Staude

‘I ASKED: WHAT ARE WE LIKE?’ Helena Waldmann on her theatre work in Iran, on prejudice, the grip of censorship - and how to let tents tell stories>

Frankfurter Rundschau: A German director who works in Iran – that’s so unusual that I have to ask: how much previous knowledge did you have when you went?

Helena Waldmann: None. This is how I came to Iran: we wanted to send the MS Studnitz, that’s a big culture ship that’s anchored in Rostock, to the Orient. We developed concepts, I had some ideas for performances. During the Theatertreffen in Berlin last year, I met the Director of the Dramatic Arts Centre in Tehran, and I told him what I was planning to do on this ship and asked if he could imagine it coming to Iran, to the coastal cities. He seemed to like the concept. Then I was invited to give a workshop in Tehran. I wondered: how do the people live? How is the theatre? What is culture in that country? I read books but I needed more help so I went to Tehran. It’s a country behind walls, behind veils; reading the papers from start to finish doesn’t help much.

So you did the workshop.

We discovered that we could work well together and we didn’t want to just leave it at that.

How did the Iranians come to your workshop? Did they have to apply?

The director of the Dramatic Arts Centre said: these are the best ones. I thought: Oh no. (laughs) That was of course a personal decision of his, other Iranian actors are just as good. After the parliamentary elections, the director was replaced. The new bosses knew nothing of the whole story.

How did the Iranian artists respond to your way of working?

In Iran, nobody uses a performative approach. It’s true there are two young directors who work

differently, but most plays are based strongly on texts, have almost no movement, are basically bodyless. Someone sits at a table and talks, talks, talks. Theatre plays a major role in this country, it’s a mouthpiece that can be used to express opinions in a subtle way, a bit reminiscent of how it was in the GDR.

But presumably there’s also a censor. How does that work?

Normally it works so: if someone wants to stage a play, they send in their text. That wasn’t possible with Tentland because there was no text. For Iranian directors, it’s enough to say, for example: I’m taking Shakespeare, Hamlet. And if the censors find that Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a good play, they’ll approve it. We staged the play in Germany, so the censors saw it for the first time one day before the premiere. In my case, there were two censors. They had a look at it and took certain things out, for instance a dance that’s projected on a tent – actually it’s just a shadow dance, very gentle, one sees no skin, nothing. But we could only project it as a still image. If there’s no movement, it’s allowed. And we had to take the solo voice of a woman out, female solos are prohibited. The next day, it was more intense; there were nine censors. The top cheeses. Two hours before the premiere, they wanted to see the whole play, and we had to answer many questions – such as whether we would have staged it that way in other countries. The internationality was very important to them.

Something special about the play is that, at the end, women from the audience are invited to come on the stage.

Yes, and the censors couldn’t know what we were doing, because the censors are all men. So they wanted us to can it. But luckily, my assistant,who is a very famous actor in Iran, prevented them by having an outburst – crying and screaming, really! And she said they couldn’t tell me to take that part out.

When did you have the idea for the tents for „Letters from Tentland“?

Actually the first time I was in Tehran. I was surprised by how many tents there were on the side of the street. There was at the time a campaign against mice; people sat in front of the tents and gave out information on how to drive a mouse out of a house. There’s a tent in the city for every single situation. But I didn’t dare to constantly use tents during the workshop and only decided to do it at the last moment – the actors thought I was nuts. But it worked. On the one hand, one felt the extreme handicap, one had to develop a particular way of acting with the tent; on the other hand it was very funny. The tents are clumsy, like Barbapapa. We laughed till we cried, in both senses; we also played a death scene, something very serious, and it worked.

How was working with the actors?

I was not interested in going there and teaching them something, I wanted an exchange. The women were asked to write „letters“ – hence „Letters from Tentland“. And the first letter that they wrote was addressed to God. You’d have to wait a long time for that in Germany. They wrote: „Please God, come back from holiday“. The sentence is in the play, because it’s a very nice way of expressing abandonment and fear. The women could be very honest, the doors were closed behind us. We were on our own and could improvise a lot.

Was there trust from the very beginning?

At the beginning there was a lot of competition between the actors, because there’s an incredible amount of aggression in Tehran, like on the streets: the smallest space will be used, even if it doesn’t help. It might be that they get somewhere a bit faster. But in the course of time, the group came together. A very important theme was prejudice. They said to me: you’re not at all the way „they“ are. And I asked: how are „they“? Then one actress said: harsh, super strict, totally precise, not funny at all. And of course I brought a bunch of prejudices with me to Iran: the women are suppressed, they have to submit to these clothing rules …. And they said: The veil is not our main problem, there are much worse ones. You notice that it’s not easy to live in this country – at the same time, the women are incredibly happy. They just live in two worlds: internal and external. And as soon as they leave the external one, they show an incredible joy of life – and they do as they wish. In Iran, there’s everything – you just don’t see it all.

Junge Welt | 11.6.2005

Interview with Helena Waldmann by Gabriele Beck

Dance of the tents. The German-Iranian choreography “Letters from Tentland” at the Venice Biennale>

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, women are not allowed to dance, nor are they allowed to exhibit their bodies in any way. The term “dance” has been completely erased from the language. At best, “rhythmic movement” is allowed, but only if it is veiled and devoid of sensuality. In her choreography “Letters from Tentland”, German director Helena Waldmann uses the rigid rules of the Muslim theocracy, even exaggerating them by putting her performers in tents and letting them perform in them, in order to gain freedom of expression for her social criticism – despite censorship and taboos in Iran, where the piece premiered at the Fadjr Festival in Tehran. Six small, conical tents are placed on the stage and gradually reveal an enigmatic interior: First, there are isolated knocks, then shouts, and finally the tents start to move. They bend as if they were in the wind, fold into expressive figures, stand on their heads. An Iranian actress is hidden in each tent, barely recognizable behind the window-like openings. The tents function as islands in public space – both a protective refuge and an emotional prison. The “privilege of being unidentifiable”, as stated in one of the monologues, is used for ambiguous thoughts: “I make my own theater,” one defiant voice says, “this tent reminds me of the sticky envelopes of my school books, of the classroom where it was not allowed to laugh,” complains another, “I’ve had enough of having to do this today and something completely different tomorrow,” complains a third. The image of the dancing tents is symbolically charged, because the term “chador” refers both to the tent and to the item of clothing prescribed for women in public to cover themselves. This allows for many associations: the arbitrariness of the state, the oppression of women, but also the actual and possible freedom of the individual in the unrecognizable covering.

Gabriele Beck talked to the director Helena Waldmann

Question: What made you decide to create a dance theater piece in Iran of all places – do you have a special connection to the country?

The former director of the Dramatic Arts Center in Tehran invited me last year to give a theater workshop there. At the time, I only knew as much about Iran as the media here conveys, so I was quite one-sidedly informed. However, I found the prospect of exchanging ideas with Iranian colleagues appealing. The topic of the workshop was not fixed; rather, an approach between the cultures was to take place through ideas, conversations and improvisations. Usually in Iranian theater, a text is given which the actors then perform. In my workshop, on the other hand, each actress was to contribute her own thoughts, hence the working title “Letters from Tehran”. That was a little daunting for the participants, but on the other hand they were incredibly hungry for new approaches and inspiration. They addressed their “letters” to teachers and to people from whom they feel they are being watched, articulated desires and fears, talked about conformity and their search for niches in their private lives.

Question: Why did you work exclusively with women?

Because women talk more openly with each other and act more freely. You have to consider that in Iran, there is an absolute ban on contact between the sexes, both on and off the stage. In theater, language has traditionally been in the foreground, and only recently has more space been given to the body. Physical expression as a form of artistic expression is therefore rather unusual, and the inhibition threshold only increases under male eyes. Our rehearsal space was almost like a private living room, where, by the way, the official rules are also treated more loosely in real life than in public.

Question: How did you come up with the idea of having your actresses perform in tents?

In preparation for the workshop, I traveled around Iran for ten days to get impressions. One of them was these small, mobile tents that can be found in the mountains, on the side of the road, and in the green spaces of the parks. Not that the cities are full of tents, but you see them quite often. They offer shelter to refugees, for example after an earthquake, or serve as shady retreats for families at picnics or on the beach. Women in particular would never just lie on the floor, that would be too erotic, even in a coat. It was only during the workshop that I realized that the term “chador” means the same as tent or this coat, where we experimented with the tents rather by chance on the last day. We laughed our heads off at the bouncing “Babapapas” but also recognized the possibilities that this type of covering opens up for us. The tents proved to be mobile spaces that restricted the performers but also liberated them in such a way that we were sure we could “expand the boundaries of the possible” with the idea of tent theater. We decided to invent a play about life in Tentland and, with the support of the Goethe Institute and the Dramatic Arts Center, we were able to do so.

Question: “Letters from Tentland” opened the international section of the Fadjr Theater Festival in Tehran in January. The piece is designed to be socially critical – in Iran, this is not really allowed and is punished by censorship. A tightrope walk for those involved?

The theater definitely serves as a public forum for criticism of all kinds, but it just has to be encrypted. Those who don’t comply end up in jail. Seen in this light, censorship has a kind of protective function for those in charge: the festival director, the mayor and, of course, the artists. Censorship takes place before the performance, so what gets through can no longer be a disaster for those involved. The censors of the Ministry of Culture and Religious Leadership often even have a dual function, being former stage directors or actors themselves and are not always uncomprehending diehards.

Question: How do you deal with the knowledge that the censor is breathing down your neck, so to speak?

The festival director, Khosrow Neshan, gave me some initial advice: “Do your art and don’t think about the censor for the time being. The censors will decide later what can be shown in Iran.” But that’s easier said than done. The scissors in my head were already very strong. The experienced actresses on the team helped me, as they were able to give me pointers on what would work and what would not. On the other hand, there were also discussions about whether a foreign director would be allowed to do more, or whether the censors would be more lenient.

Question: Did you encounter any restrictions from the authorities when implementing “Letters from Tentland”?

Two censors came to the dress rehearsal. We had to cut a video scene in which a dancer could be seen as a shadow figure, and we had to make a solo song very quiet so that it could hardly be heard. In Iran, women on stage must wear a coat and headscarf, and their arms must be covered up to the wrist to avoid any hint of eroticism. The dancing tents were abstract enough for the censors, only the lighting had to be checked so that the performers were not visible as shadows inside. Two hours before the premiere, another eight censors came, watched a run-through and then asked a lot of questions: Would you have been able to stage this piece in England as well? Why are only women in the play? Would it have been possible to cast only men in the play? I answered their questions and my whole team was behind me. I assume they wanted to cover themselves, because the piece with the dancing women in tents caused unrest; it had to be political somehow.

Question: The images may be ambiguous, but the language communicates quite directly. Why wasn’t the text censored more heavily?

I’ve asked myself that too. The texts are in English, but they had to be translated into Farsi and were certainly also passed on to the censors. I explain it to myself as follows: the statements and thus also the criticism is always directed at the director, at the instance that has established the rules of this game, not at the audience, at society. I make a clear appearance at the beginning of the piece and remain a communication partner for the performers on stage. So they can criticize that I bring prejudices with me, that I put them in tents and thereby make them into objects. But also that it can have advantages to be in such a tent. You are not identifiable.

Question: How did you work with the performers in terms of their different cultural backgrounds?

There were actually an incredible number of misunderstandings, and not only of a linguistic nature. For example, there were the rules, which are constantly changing in Iran. This leads to a rather arbitrary attitude in people, even in everyday life, along the lines of: if I agree to something today, I don’t necessarily have to stick to it tomorrow. This leads to problems when working together, for example with regard to punctuality. We had our struggles in that regard. Or the chaos in Tehran, a metropolis of 14 million. I remember one day when an actress had her wallet stolen on the way to rehearsal, the second had a minor car accident and the third had lost a shoe, and everyone was in a flurry. Sometimes, as a director, I had no choice but to improvise. In addition, two of the actresses are very well-known television actresses in Iran, while others are still largely unknown. Envy and competition also came into play. But after a year of working together, I would describe us all as friends today.

Question: As a foreigner, do you have a different perspective on Iranian society than the locals?

Of course I tried not to fall into the trap of prejudice. For example, I was concerned about letting the actresses slip into tents. I thought they would accuse me of thinking in clichés about poor, oppressed women in Iran. They themselves are not that bothered by it, it’s normal, they grew up that way. People don’t want to constantly politicize either, you just come to terms with the system. In this respect, the population has developed an extremely high level of inventiveness. However, it was only with the advent of the internet that most people gained access to the world; Iranian web logs are virtually exploding. Young people are more dissatisfied.

Question: Speaking of clichés: Did you find yourself holding preconceived opinions?

Working with the actresses in “Letters from Tentland” gave me insights into a world that has been more obscured in Europe by the media and clichés than it has been informed by life in that society. For example, I wanted to incorporate a terrorist scene à la “Kill Bill” into the piece. The performers intervened, they didn’t want any suicide bomber nonsense, they said it would distort reality, not every Iranian woman walks around with a bomb under her chador. That’s when you realize that you almost automatically fall back on the one-sided images from TV. I also learned a lot about hospitality.

Question: The play premiered in Tehran and was performed in Germany beforehand. What was the audience’s reaction?

In Iran, this kind of theater with various media – video projections, sounds, text and dance – is something new and therefore interesting for the audience for that reason alone. However, the images, which everyone in Iran could effortlessly interpret, turned out to be too ‚Persian‘ for Europe, that is, too indirect. Since most people here know little about Iran, the desire for more specific information was expressed. There is no conception of the difficulties that theater in Iran is confronted with. And how much the work is influenced by this, how important it is to find images for what cannot be said directly. At the end of the play, we invited the women from the audience behind the curtain on stage, which was well received each time. We sat on cushions on the floor and drank tea, continuing our cultural exchange – a kind of postscript, as it sometimes appears at the end of a letter.

Politik-Forum | 2006

Interview with Helena Waldmann by Christoph Quarch

The language of the body is universal. Dance is political. Because where there is dancing, people come into contact with each other>

A conversation with the choreographer Helena Waldmann

publik-forum: Since you had Iranian women dance on stage in your choreography “Letters from Tentland”, you have had the reputation of having given contemporary dance theater a political dimension. Are you a political choreographer?

Helena Waldmann: Many of my choreographic works have a political color. But that is not necessarily intentional, but often simply has to do with their genesis. “Letters from Tentland” was created in Iran. The actresses with whom I did a workshop there had explicitly asked me not to work with them on any political content. They said they were tired of always having to do politics with Europeans – that they just want to live, love and laugh. That made sense to me, and I tried to fulfill their request. But as soon as we started improvising, politics came into play. How could it be otherwise? If you live in a country like Iran, it is not possible to just laugh, love and live. Every utterance speaks of the oppression of the people.

publik-forum: It is clear that in Iran dance quickly becomes political. But does that also apply to our latitudes? So a more general question: What gives a choreography a political slant?

Waldmann: The choice of subject is crucial: what the dance is supposed to discuss. Recently, I staged a choreography in Saarbrücken entitled “Crash” that dealt with the issue of migration. The way the dance was performed here made something clear: the extreme physical brutality that people experience when they are turned away at borders. Expressing this with the body gives a dance political impact.

publik-forum: Is it possible to say things in the language of dance that cannot be expressed in the spoken language?

Waldmann: Yes, although I have to add that sometimes it is also more difficult to express something in dance. We humans are used to understanding the world through words. That is why the direct route is through language to the mind. But you cannot tap into the emotional side of things that way. It is better conveyed through the body. That was the case in Crash, when people get stuck at the fence, as it were; or in “Letters from Tentland” through the highly emotional image of women being trapped in tents and unable to get out of them.

publik-forum: Please tell us a little more about this choreography! What is the story behind “Letters from Tentland”? You were the first European to come up with the idea of rehearsing a choreography with Iranian women.

Waldmann: The reason for this is that women in Iran are not allowed to dance in public. So it was somewhat absurd to invite me to rehearse a choreography there. But I was tempted by the idea, and so I took it on. When we developed the piece in Tehran, the current president Ahmadinejad was not yet in power. So we were able to make a difference and accomplish “the miracle of Chadorestan,” as the German weekly newspaper “Die Zeit” called it. We actually managed to put on two performances in Tehran. After that, we toured for another three months.

publik-forum: What happens in the piece?

Waldmann: Six women are moving around in tents. That was a trick, because in Iran it is forbidden for women to dance in public. However, it is not forbidden for tents in which women are to dance in public. And that’s exactly what happens on stage: tents dance. Nevertheless, it had a provocative political component, which I only became aware of later: The word “chador” means both “dress” and “tent.” And so the Iranian audience assumed that the tents are a symbol for the chador that women are forced to wear in public. But that was not my original intention. I was inspired instead by the many tents on the outskirts of Tehran, where people who have come to the city from the countryside live.

publik-forum: And what theme did you want to convey with it?

Waldmann: I was concerned with the topic of public and private life. In Iran, people lead two lives. One is inside, the other is outside. You need that to avoid going crazy in this country. People need places to which they can withdraw to find a counterweight to the hypocrisy of public life. In public, you can’t say anything, you can’t show anything: Every open word is dangerous. But there is another life, the real life, where you can show your face. This life takes place undercover: in houses, in apartments, in back rooms. This inner life is true. That is what the dancers wanted to express.

publik-forum: The inner life behind the shell of the tent?

Waldmann: Exactly. The real life is veiled. And I have experienced in Iran that this life is much more extreme and sometimes also much more fun and lively than here. When I was invited to private homes, I experienced a great liveliness and zest for life there: bursting, quivering bodies, dancing and fun without end. I hardly find that here at all.

publik-forum: You performed “Letters from Tentland” all over the world. Then one day the piece was called “Return to Sender”. What happened?

Waldmann: After a year and three months, we received a real letter from “Tentland”, that is, from Tehran. Our Iranian dancers asked us to give up the piece. With the election of Ahmadinejad, conditions in Iran had changed, and our women there felt threatened. On the one hand, I didn’t want to endanger them, but on the other hand, I didn’t want to let Iran dictate which pieces I was allowed to show. So I cast Iranian women living in Berlin and asked them if it would be interesting for them to rewrite this piece, so to speak. That’s how “Return to Sender” came about.

publik-forum: What was new about it?

Waldmann: The symbolism changed due to the completely different situation of the Iranian women in exile: the tents now became images of the uncertain situation of these women, who are always on the go and have to expect deportation. But the veiling motif was also important for the women. I realized that they longed for veiling so as not to always be perceived as foreigners. And so the Iranians living in Germany wrote their “letters to the sender” and described their situation in exile to their sisters in Tehran.

publik-forum: It is amazing that these different life situations can be expressed with the same visual language – and that this language is understood by people all over the world. Is dancing something like a universal language?

Waldmann: Absolutely. Body language is everywhere and always present. And through it, people of the most diverse cultural backgrounds can communicate.

publik-Forum: But there are major differences: people in Japan dance quite differently than in Africa, and Latinos dance differently than Indians.

Waldmann: The different dance forms tell something about the different cultures in which people live. And yet you can decipher what they express in their own way. Because, despite all cultural differences, body language is ultimately one and the same.

publik-forum: Then dance would be a wonderful means of communication in a globalized world.

Waldmann: That’s right. And you know, I am convinced that dance is a medium in which cultures and religions can communicate with each other – a language in which Muslims and Christians, Jews and Buddhists can communicate.

publik-forum: But they rarely do. Why?

Waldmann: Because we – especially in Germany – have lost the sense of expressing ourselves through dance. People hardly dance anymore. They may watch dance films at the cinema or dance performances at the theater and opera, but they have lost touch with their own bodies and forgotten their language. It would be good if people in this country rediscovered what it means to lose your head sometimes.

publik-forum: How do you intend to teach our contemporaries this?

Waldmann: People have to relearn how to take responsibility and become active: not sit in front of the television or in the auditorium and let others dance, act, cook. What would it be like to say: We’ll do it ourselves!

publik-forum: But people do dance. Tango is very popular, and hundreds of thousands of people go raving at the Love Parade. It’s not as if people in Germany don’t dance.

Waldmann: That’s true, but in the end, it’s still a minority that dances, in my opinion. And even then, there’s often a lack of appreciation for the fact that dance is communication. I don’t want to say that only couple dancing is real dancing. You can also communicate with your body in other ways through dancing. What is important is that you have the interest in “talking” to another person through dancing. And that is what I miss in this country. People hardly look each other in the eye, they close themselves more and more. How can you expect them to dance with each other? They don’t.

publik-forum: Which brings us back to the tents.

Waldmann: Exactly. But now comes the crucial point: in the tents, behind the veils, there is a rumbling and pulsating. There is a cry for freedom. There is a wandering soul that dances and whirls wildly. In “Letters from Tentland,” a woman spun around in her tent like a dervish. That was her way of calling on God. In such moments, dance becomes a highly spiritual activity. I don’t know if the audience in Germany perceived this, but in Iran and other Islamic countries, people were aware that they were witnessing a spiritual dance.

publik-forum: Did your dancers see it that way too?

Waldmann: They repeatedly emphasized that they have an intense relationship with God and want to express that. But not in the ritualized forms of prostration and the like. They called upon God with their individual, improvised dance. I found that very beautiful.

publik-forum: Dancing – the spiritual antidote in a world poor in communication. Is this the thesis behind your new choreography “feierabend! – das gegengift ” (after work party – the antidote )?

Waldmann: Not the antidote, but a definite possibility. For me, dancing always means celebrating as well: and celebrating is something else we have to rediscover in this country. People in Germany are totally fixated on work – and often don’t know what to do with their free time. This is the theme of my latest choreography. It is about celebrating as a counterbalance to work. But a good party always includes dancing. Because dancing is a way of simply switching off your brain for a while. The brain is the entrance fee. If you want to join the party of life, it will cost you your brain – or at least your wits.

german

Frankfurter Rundschau | 12.10.2005

Interview mit Helena Waldmann von Sylvia Staude

"ICH HABE GEFRAGT: WIE SIND WIR DENN?" Helena Waldmann über ihre Theaterarbeit in Iran, über Vorurteile, den Zugriff der Zensur - und wie man Zelte Geschichten erzählen lassen kann>

Frankfurter Rundschau: Eine deutsche Regisseurin, die in Iran arbeitet – das ist so ungewöhnlich, dass ich mich fragte: Mit welchem Vorwissen sind Sie dorthin gereist?

Helena Waldmann: Ich hatte keins. Gekommen ist das mit Iran so: Wir hatten vor, die MS Studnitz, ein großes Kulturschiff, das in Rostock liegt, in den Orient zu schicken, es wurden Konzepte gemacht, ich habe Inszenierungsideen entwickelt. Als dann das Theatertreffen war, im vergangenen Jahr, war der Leiter des Teheraner Dramatic Arts Centre in Berlin, und ich habe ihm erzählt, was ich auf diesem Schiff machen würde und ob er sich vorstellen könnte, dass es auch in den Iran kommt, in die Küstenstädte. Das Konzept scheint ihm gefallen zu haben. Daraufhin bin ich eingeladen worden, in Teheran einen Workshop zu geben. Ich habe mich gefragt: wie leben die Leute, wie ist das Theater, was ist die Kultur in diesem Land. Bücher habe ich auch gelesen, aber ich brauchte mehr Hilfe, so bin ich nach Teheran gereist. Es ist ein Land hinter Mauern, hinter Schleiern, da nützt es nicht viel, die Zeitung rauf und runter zu lesen.

Sie haben dann also den Workshop gemacht.

Wir stellten fest, dass wir gut zusammenarbeiten konnten und wollten das Ergebnis nicht auf sich beruhen lassen.

Wie kamen die Iranerinnen in Ihren Workshop? Mussten sie sich bewerben?

Der Leiter des Dramatic Arts Centre hat mir gesagt: Das sind die Besten. Ich dachte: Oh je (lacht). Das war natürlich eine persönliche Entscheidung von ihm, andere iranische Schauspielerinnen sind genauso gut. Nach den Parlamentswahlen wurde dieser Leiter abgesetzt, die neuen Chefs wussten von der ganzen Angelegenheit nichts.

Wie wurde Ihr Arbeitsstil von den iranischen Künstlerinnen aufgenommen?

Im Iran kennt man performative Ansätze nicht. Es gibt zwar zwei junge Regisseure, die anders arbeiten, aber die meisten Stücke basieren ganz stark auf Text, enthalten fast keine Bewegung, sind quasi körperlos. Man sitzt an einem Tisch und redet, redet, redet. Theater spielt eine große Rolle in diesem Land, es ist ein Sprachrohr, durch das man seine Meinung sagt, aber eher zwischen den Zeilen, wie wir das aus der DDR kennen.

Es gibt vermutlich auch eine Zensur, wie funktioniert sie?

Normalerweise ist es so: Wenn man ein Stück inszenieren will, reicht man den Text ein. Das ging bei Tentland nicht, es gab keinen Text. Für iranische Regisseure genügt es, dass sie zum Beispiel sagen: Ich nehme Shakespeare, Hamlet. Und wenn die Zensoren finden, dass Shakespeares Hamlet ein gutes Stück ist, dann wird es eben genommen. Wir haben das Stück in Deutschland fertig inszeniert; und so kamen die Zensoren auf dem Teheraner Festival erst einen Tag vor der Premiere. In meinem Fall waren zwei Zensoren da. Die haben sich das angeguckt und dann Sachen rausgenommen, zum Beispiel einen Tanz, der projiziert wird auf die Zelte – eigentlich nur ein Schattentanz, ganz zart, man sieht keine Haut und gar nichts. Das durften wir nur als Standbild projizieren; denn wenn keine Bewegung dabei ist, geht es. Und wir mussten die Solostimme einer Frau rausnehmen, weiblicher Solo-Gesang ist verboten. Einen Tag später wurde es heftiger, da kamen nochmal neun Zensoren. Die wichtigsten der wichtigen. Zwei Stunden vor der Premiere haben sie sich das ganze Stück vorspielen lassen, wir mussten viele Fragen beantworten – etwa, ob ich das in einem anderen Land auch so inszeniert hätte. Diese Internationalität war für sie sehr wichtig.

Etwas Besonders an Ihrem Stück ist, dass am Ende die Frauen im Publikum eingeladen werden, auf die Bühne zu kommen.

Ja, da konnten die Zensoren nicht wissen, was wir da machen, denn die Zensoren sind alle Männer. Sie wollten das also streichen. Zum Glück hat das meine Regieassistentin, die in Iran eine sehr berühmte Schauspielerin ist, verhindert, indem sie Heul- und Schreianfälle bekam – wirklich! Und erklärte, das könne sie mir auf keinen Fall sagen, dass das raus soll.

Wann hatten Sie die Idee mit den Zelten für „Letters from Tentland“?

Eigentlich schon, als ich das erste Mal in Teheran war. Mir ist aufgefallen, dass in Iran viele Zelte am Straßenrand stehen. Es gab gerade eine Kampagne gegen Mäuse, da saßen Menschen vor den Zelten und informierten darüber, wie man die Mäuse aus dem Haus bekommt. Für alle möglichen Situationen gibt es Zelte in der Stadt. Ich habe mich aber während des Workshops nicht getraut, dauernd Zelte zum Einsatz zu bringen und habe mich erst im letzten Moment dazu entschlossen – die Darstellerinnen hatten gedacht, ich habe einen Knall. Aber es hat funktioniert: Man hat einerseits die extreme Behinderung gespürt, denn man muss ja eine ganz neue Spielweise entwickeln, andererseits war es sehr lustig. Die Zelte sind purzelig wie Barbapapa. Wir haben Tränen gelacht, im doppelten Sinn, denn wir haben auch eine Todesszene gespielt, etwas sehr Ernstes, und es funktionierte.

Wie war die Mitwirkung der Darstellerinnen?

Mein Interesse war nicht, da hinzugehen und irgendwas zu unterrichten, ich wollte den Austausch. Die Frauen sollten „Briefe“ schreiben, deswegen Letters from Tentland. Und der erste Brief, den sie geschrieben haben, ging an Gott. Darauf müsste man in Deutschland lange warten. Sie schrieben: „Please God, come back from holiday“. Der Satz ist im Stück, denn er ist eine schöne Art, Verlassenheit und Angst auszudrücken. Die Frauen konnten sehr ehrlich sein, die Türen waren ja hinter uns zu. Und wir waren unter uns, haben viel improvisiert.

War das Vertrauen von Anfang an da?

Anfangs war die Konkurrenz zwischen den Schauspielerinnen groß, wie ja auch in Teheran eine unglaubliche Aggressivität herrscht, etwa auf den Straßen: Da wird die kleinste Lücke genutzt, auch wenn man weiß, es bringt gar nichts. Könnte ja sein, dass man doch ein bisschen schneller ist. Aber im Lauf der Zeit ist die Gruppe zusammengewachsen. Ganz wichtig war da auch das Thema Vorurteile. Sie sagten zu mir: Du bist gar nicht so, wie ihr seid. Und ich habe gefragt: Wie sind wir denn? Da sagte mir eine Darstellerin: Harsch, superstreng, obergenau, überhaupt nicht lustig. Aber natürlich habe ich andersrum auch Vorurteile mitgebracht in das Land: Die Frauen sind unterdrückt, sie müssen sich der Kleiderordnung unterwerfen …. Und sie haben mir gesagt: Das Kopftuch ist nicht unser größtes Problem, da gibt es viel schlimmere. Man merkt, es ist nicht leicht, in diesem Land zu leben – gleichzeitig sind es unglaublich glückliche Frauen. Sie leben einfach in zwei Welten: im Innen und im Außen. Und in dem Moment, in dem sie das Außen verlassen, zeigen sie ihre große Lebensfreude – und machen, was sie wollen. Im Iran gibt es nichts, was es nicht gibt, man sieht es nur nicht.

DER TAGESSPIEGEL |18.10.2005

Interview mit Helena Waldmann von Sandra Luzina

Verdeckte Ermittlungen. Frauen dürfen im Iran nicht öffentlich tanzen. Wie die Choreografin Helena Waldmann mit dem Verbot spielt>

Der Brief kam aus Teheran. Er erreichte Helena Waldmann in Salvador de Bahia, wo sie gerade an einem Stück arbeitete. Das Schreiben war eine Einladung: Die Regisseurin, die für ihre ungewöhnlichen Aufführungen im Grenzbereich von Tanz und Theater bekannt ist und einmal über die Idee einer Theaterkarawane zwischen Orient und Okzident fantasiert hatte, sollte einen Workshop in Teheran geben. Sie sagte zu. Da wusste sie noch nicht, was sie erwartet. Sie wusste nur: Im Iran ist den Frauen das Tanzen in der Öffentlichkeit verboten. Es gibt nicht einmal ein Wort dafür. Offiziell ist nur von „rhythmischer Bewegung“ die Rede. „Das war natürlich ein Aspekt, der mich extrem gereizt hat“, erklärt Waldmann lächelnd.

Bei dem Workshop blieb es nicht. Die Berlinerin ist die erste deutsche Choreografin, die ein Stück im Iran erarbeitet hat. „Letters from Tentland“ heißt es und ist nicht nur ein Politikum, sondern vor allem ein exzeptionelles Theaterereignis. Die Karawane, von der Helena Waldmann träumte, ist wirklich losgezogen. Auf internationalen Festivals gefeiert, macht sie nun an zwei Abenden an der Berliner Schaubühne Halt. Es war ein weiter Weg.

Der europäische Blick auf den Orient ist meist vom Schleier und dem Geheimnis – oder erotischen Versprechen – gefesselt, das ihn umgibt. Doch Helena Waldmann weist auch den aufgeklärten Enthüllungsgestus zurück. Sie zeigt uns nicht die Welt hinterm Schleier. Stattdessen betätigt sie sich als raffinierte Verpackungskünstlerin – und als verdeckte Ermittlerin. Geprobt wurde hinter verschlossenen Türen – davor warteten die Zensoren. Waldmann ermutigte die Darstellerinnen, sich nicht vorschnell selbst zu zensieren und auszuprobieren, was möglich ist. Und war dann von deren Erfindungsgeist verblüfft. „Sie arbeiten permanent daran, die Grenzen des Möglichen zu erweitern“, weiß Waldmann.

Im Stadtbild von Teheran waren der Regisseurin die kleinen Zelte aufgefallen, angeregt durch dieses objet trouvé bittet sie die Darstellerinnen, in Zelte zu schlüpfen. „Zunächst schlugen alle die Hände über dem Kopf zusammen“, erzählt die Regisseurin. „Helena, das geht nicht!“, protestierten die Akteurinnen. Doch sie insistierte und schuf eine Versuchsanordnung, die konsequent ausgereizt wird. Denn raus dürfen die Frauen nicht, bis zum Schluss lüften sie ihre Identität nicht. Eine Herausforderung: Die Darstellerinnen mussten nicht nur ausprobieren, wie man sich in den „mobilen Räumen“, bewegen kann, sie mussten vor allem lernen, mit der Beengung kreativ umzugehen. „Wir mussten ein neues Theateralphabet lernen“, sagt die Regisseurin. So entfaltet das Zelt-Experiment auf der Bühne seinen eigenen Reiz. Sechs Stoffgehäuse stehen zu Beginn aufgereiht an der Rampe wie eine kleine Festung – aus kleinen Gitterfenstern blicken dunkle Augenpaare.

Am Ende steht nur noch ein schwarzes Zelt da, das alle anderen verschluckt hat. Ein eigenartiger Tanz ist dem vorausgegangen, die luftigen Stoffhüllen schweben, schwanken und überschlagen sich, sie stehen Kopf, und immer mal tanzt eins aus der Reihe. Die Stimmen und Zeichen, die aus dem Innern dringen, lassen sich nicht gleich deuten. Es sind – wie der Titel sagt – „Briefe“ aus einem rätselhaften Land, deren Botschaften man erst entschlüsseln muss. Man sieht sich mit einer Kultur konfrontiert, die für westliche Betrachter nicht unmittelbar lesbar ist. Mehr noch: Die Absenderinnen dieser Briefe bleiben bis zuletzt unsichtbar. So schafft Waldmann ein treffendes Bild für die Situation der Frauen unterm Mullah- Regime.

Die Konstruktion von Blicken ist zentral für Helena Waldmanns Inszenierungen. Insofern sind die „Letters from Tentland“ für sie eine logische Fortsetzung ihrer bisherigen Arbeit. „Ich habe schon oft Darsteller eingesperrt, hinter Spiegeln und Plastikfolien verborgen oder zu zweidimensionalen Figuren zusammengedrückt. Dass ich die Frauen nun in Zelte gesteckt habe, ist nicht nur ein ästhetischer Trick, sondern ein Mittel, um etwas aufsprengen, um Dinge auszusprechen, die ich sonst nicht hätte sagen können.“

Im Schutz der Anonymität lässt sich Klartext reden. „Die Zelte sind wie Briefumschläge, womit die Darstellerinnen sie füllen, blieb ihnen überlassen“, erklärt die Regisseurin, die zur stellvertretenden Machtinstanz wird, zum Regime an Stelle des Regimes: Sie ändere ständig die Regeln, nach denen sie agieren müssen, sagen die Frauen. Und indem die Choreografin sie in Zelte verbanne (das Wort „Tschador“ bezeichnet im Persischen sowohl das Zelt als auch den Schleier), verhülle sie sie gleichsam ein zweites Mal. Was sich in dieser verborgenen Welt abspielt, entzieht sich unserer Wahrnehmung. Aber wir erfahren, wie die Frauen sich mit List und Fantasie gegen das Unsichtbar-Sein wehren. Und dass sich ihre Tanzlust, ihre Ausdruckswut nicht bändigen lässt.

„Letters from Tentland“ wurde zum Wendepunkt in Waldmanns künstlerischer Biografie. „Durch die Arbeit habe ich nicht nur einen tiefen Einblick in eine total fremde Kultur bekommen, ich habe auch neue künstlerische Perspektiven gewonnen“, erklärt die Regisseurin.

Jedenfalls hat sie sich damit für schwierige Jobs im Parcours des internationalen Kulturaustauschs qualifiziert. Der führte sie im Mai 2005 nach Ramallah, wo sie im Auftrag des Goethe-Instituts mit der palästinensischen El-Fonoun Dance Troup einen Tanzdokumentarfilm drehte: „Emotional Rescue“. Wieder war die Regisseurin ohne fertiges Konzept angereist. Den Darstellern sagte sie: „Ich möchte ein Stück mit euren Geschichten machen.“ Die kreisen alle um das Thema Besatzung und Unterdrückung, so dass die Regisseurin erneut eine Sprache dafür finden musste, eingesperrt zu sein. „Es sind Geschichten von Behinderung und Nicht-Bewegung, von totalem Stillstand und Hoffnungslosigkeit“, sagt Waldmann.

Doch ihre Figuren tanzen. Es ist der Traum von Freiheit, der zum Movens wird, und so einfach wie wahr: Fantasie kann man nicht einsperren. In „Letters from Tentland“ ist einmal ein tanzender Schatten zu erkennen, wie ein fernes Echo dringt ein betörender Gesang ans Ohr.

Junge Welt | 11.6.2005

Interview mit Helena Waldmann von Gabriele Beck

Tanz der Zelte. Die deutsch-iranische Choreografie „Letters from Tentland" auf der Biennale in Venedig>

In der islamischen Republik Iran ist Tanzen für Frauen verboten, so wie jegliche Zurschaustellung des Körpers. Der Begriff „Tanz“ wurde ganz aus dem Sprachgebrauch gestrichen, allenfalls „rhythmische Bewegung“ ist erlaubt, die sich jedoch verschleiert und bar jeder Sinnlichkeit präsentieren muss. Die deutsche Regisseurin Helena Waldmann nutzt die rigiden Regeln des muslimischen Gottesstaates in ihrer Choreografie „Letters from Tentland“, überhöht sie sogar, indem sie ihre Darstellerinnen in Zelte steckt und darin auftreten lässt, um sich inhaltlichen Freiraum zur Gesellschaftskritik zu verschaffen – trotz Zensur und Tabus im Iran, wo das Stück am Fadjr-Festival in Teheran Premiere hatte. Sechs kleine, konisch zulaufende Zelte stehen auf der Bühne und entfalten nach und nach ein rätselhaftes Innenleben: Erst ertönen einzelne Klopfzeichen, dann Rufe, schließlich geraten die Zelte in Bewegung. Sie biegen sich, als stünden sie im Wind, falten sich zu expressiven Figuren, stehen auf dem Kopf. In jedem Zelt verbirgt sich eine iranische Darstellerin, hinter den fensterartigen Öffnungen kaum zu erkennen. Die Zelte fungieren als Inseln im öffentlichen Raum – zugleich schützende Zuflucht als auch emotionales Gefängnis. Das Privileg, nicht identifizierbar zu sein“, wie es in einem der Monologe heißt, wird genutzt für doppeldeutige Gedanken: Ich mache mein eigenes Theater“, hört man eine trotzige Stimme, dies Zelt erinnert mich an die klebrigen Umschläge meiner Schulbücher, an das Klassenzimmer, wo es nicht erlaubt war zu lachen“, beklagt sich eine andere, ich habe genug davon, heute dies und morgen etwas ganz anderes tun zu sollen“, beschwert sich eine dritte. Das Bild der tanzenden Zelte ist symbolisch aufgeladen, denn der Begriff „Tschador“ bezeichnet sowohl Zelt“ als auch das in der Öffentlichkeit vorgeschriebene Kleidungsstück zur Verhüllung der Frauen. Das lässt viele Assoziationen zu: die Willkür des Staates, die Unterdrückung der Frau aber auch die tatsächliche und mögliche Freiheit des Individuums in der unkenntlich machenden Hülle.

Gabriele Beck sprach mit der Regisseurin Helena Waldmann

Frage: Wie kamen Sie dazu, ausgerechnet im Iran ein Tanztheater zu erarbeiten – haben Sie einen speziellen Bezug zu dem Land?

Der damaligen Leiter des Dramatic Arts Center in Teheran lud mich letztes Jahr ein, dort einen Theater-Workshop zu geben. Damals wusste ich über den Iran nur so viel, wie die Medien hier übermitteln, war also recht einseitig informiert. Allerdings fand ich die Aussicht reizvoll, mich mit iranischen Kolleginnen und Kollegen austauschen zu können. Das Thema des Workshops war nicht festgelegt, vielmehr sollte über Ideen, Gespräche und Improvisationen eine Annäherung der Kulturen stattfinden. Üblicherweise wird im iranischen Theater ein Text vorgegeben, welchen die Schauspieler vortragen. In meinem Workshop dagegen sollte sich jede Darstellerin mit eigenen Gedanken einbringen, daher auch der Arbeitstitel „Letters from Teheran“. Das war für die Teilnehmerinnen schon etwas beängstigend, andererseits hatten sie einen unglaublichen Hunger nach neuen Arbeitsansätzen und Anregungen. Sie richteten ihre „Briefe“ an Lehrer und an Personen, von denen sie sich beobachtet fühlen, artikulierten Wünsche und Ängste, erzählten über Anpassung und ihre Suche nach Nischen im Privaten.

Frage: Warum haben Sie ausschließlich mit Frauen gearbeitet?

Weil Frauen untereinander einfach offener reden und sich freier bewegen. Man muss bedenken: Im Iran herrscht sowohl auf der Bühne wie auch außerhalb des Theaters absolutes Berührungsverbot zwischen den Geschlechtern. Auch steht im Theater die Sprache traditionell im Vordergrund, dem Körper wird erst in letzter Zeit mehr Raum gegeben. Körpereinsatz als künstlerische Ausdrucksform ist daher eher ungewohnt, da steigt die Hemmschwelle unter männlichen Blicken nur. Unser Probenraum war fast wie ein privates Wohnzimmer, wo mit den offiziellen Regeln übrigens auch im wirklichen Leben lockerer umgegangen wird als in der Öffentlichkeit.

Frage: Wie kamen Sie auf die Idee, ihre Darstellerinnen in Zelten agieren zu lassen?

Als Vorbereitung auf den Workshop bin ich zehn Tage durch den Iran gereist, um mir Eindrücke zu verschaffen. Einer davon waren diese mobilen, kleinen Zelte, die in den Bergen, am Straßenrand, in den Grünflächen der Parks stehen. Nicht dass die Städte voller Zelte wären, aber man sieht sie doch recht häufig. Sie bieten Flüchtlingen Unterschlupf, etwa nach einem Erdbeben, oder dienen den Familien als schattige Rückzugsmöglichkeiten beim Picknick oder am Strand. Vor allem Frauen würden sich nie einfach auf den Boden legen, das wäre zu erotisch, selbst im Mantel. Dass der Begriff „Tschador“ dasselbe bedeutet wie Zelt oder eben diesen Mantel, ging mir erst beim Workshop auf, wo wir am letzten Tag eher zufällig mit den Zelten experimentiert haben. Wir haben Tränen gelacht über die hopsenden Babapapas“ aber auch die Möglichkeiten erkannt, die uns diese Art der Verhüllung eröffnet. Die Zelte erwiesen sich als mobile Räume, die die Performerinnen zwar einschränkten, aber auch so befreiten, dass wir sicher waren, mit der Idee des Zelttheaters «die Grenzen des Möglichen erweitern» zu können. Wir beschlossen, ein Stück über das Leben in Tentland zu erfinden und mit Unterstützung des Goethe Instituts und des Dramatic Arts Center war das auch möglich.

Frage: „Letters from Tentland“ eröffnete im Januar die internationale Sektion des Fadjr-Theaterfestival in Teheran. Das Stück ist gesellschaftskritisch angelegt – im Iran ist das eigentlich nicht erlaubt und wird durch die Zensur geahndet. Eine Gratwanderung für die Beteiligten?

Das Theater dient durchaus als öffentliches Forum für Kritik jeglicher Art, nur muss das eben verschlüsselt geschehen. Wer sich nicht daran hält, landet im Gefängnis. So gesehen hat die Zensur eine Art Schutzfunktion für die Verantwortlichen: den Festivalleiter, den Bürgermeister und natürlich die Künstler. Zensiert wird vor der Aufführung, was durchkommt, kann den Beteiligten nicht mehr zum Verhängnis werden. Die Zensoren des Ministeriums für Kultur und religiöse Führung haben oft sogar eine Doppelfunktion, sind selbst ehemalige Regisseure oder Schauspieler und nicht immer unverständige Betonköpfe.

Frage: Wie geht man mit dem Wissen um, dass einem die Zensur sozusagen im Nacken sitzt?

Der Leiter des Festivals, Khosrow Neshan, gab mir zu Anfang den Rat: Machen Sie Ihre Kunst und denken Sie erst mal gar nicht an die Zensur. Die Zensoren werden später entscheiden, was im Iran gezeigt werden darf.“ Aber das ist leichter gesagt als getan. Die Schere in meinem Kopf war schon sehr stark. Da halfen mir die erfahrenen Schauspielerinnen im Team, die mir Anhaltspunkte geben konnten, was geht und was eher nicht. Andererseits gab es auch Diskussionen, ob man mit einer ausländischen Regisseurin nicht mehr wagen könne, ob die Zensoren vielleicht milder urteilen würden.

Frage: Sind Sie bei der Umsetzung von „Letters from Tentland“ auf Grenzen seitens der Behörden gestoßen?

Zur Generalprobe kamen zwei Zensoren. Eine Videoszene, in der eine Tänzerin als Schattenfigur zu sehe war, mussten wir herausschneiden und einen Sologesang ganz leise stellen, so dass er kaum noch zu hören war. Im Iran müssen die Frauen auf der Bühne Mantel und Kopftuch tragen und die Arme müssen bis zum Handgelenk verhüllt sein, damit nur ja keine Erotik aufkommt. Die tanzenden Zelte waren den Zensoren abstrakt genug, nur auf die Beleuchtung mussten wir achten, damit die Darstellerinnen im Inneren nicht als Schatten sichtbar waren. Zwei Stunden vor der Premiere kamen dann nochmals acht Zensoren, sahen sich einen Durchlauf an und stellten anschließend viele Fragen: Hätten Sie dieses Stück auch in England inszenieren können? Warum spielen nur Frauen in dem Stück? Wäre es auch möglich gewesen das Stück nur mit Männern zu besetzen? Ich stand Rede und Antwort und mein ganzes Team hinter mir. Ich nehme an, die wollten sich untereinander absichern, denn das Stück mit den tanzenden Frauen in Zelten sorgte für Unruhe, das musste irgendwie politisch sein.

Frage: Die Bilder mögen zweideutig sein, es wird aber recht direkt über die Sprache kommuniziert. Warum wurden die Texte nicht stärker zensiert?

Das habe ich mich selbst auch schon gefragt. Die Texte sind zwar auf Englisch, mussten aber auf Farsi übersetzt werden und wurden sicherlich auch an die Zensoren weitergeleitet. Ich erkläre mir das folgendermaßen: die Aussagen und damit auch die Kritik ist immer direkt an die Regisseurin gerichtet, an die Instanz, die die Regeln dieses Spiels etabliert hat, nicht an das Publikum, also die Gesellschaft. Ich trete am Anfang des Stückes klar in Erscheinung und bleibe Kommunikationspartnerin für die Darstellerinnen auf der Bühne. So können sie kritisieren, dass ich Vorurteile mitbrächte, dass ich sie in Zelte stecke und sie dadurch zum Objekt werden lasse. Aber auch, dass es durchaus Vorteile haben kann, in solch einem Zelt zu stecken. Man ist nicht identifizierbar.

Frage: Wie gestaltete sich die Zusammenarbeit mit den Performerinnen hinsichtlich des unterschiedlichen kulturellen Hintergrundes?

Es gab tatsächlich unglaublich viele Missverständnisse nicht nur sprachlicher Natur. Da war zum Beispiel der Umgang mit Regeln, die sich im Iran ständig ändern. Das führt bei den Leuten zu einer eher willkürlichen Haltung auch im Alltag, nach dem Motto: wenn ich heute etwas zusage, muss ich mich morgen nicht unbedingt daranhalten. Das ergibt bei der Zusammenarbeit Probleme zum Beispiel was die Pünktlichkeit betrifft. Da hatten wir schon miteinander zu kämpfen. Oder das Chaos in der 14-Millionen-Metropole Teheran. Ich erinnere mich an einen Tag, da wurde einer Schauspielerin auf dem Weg zur Probe das Portemonnaie gestohlen, die zweite hatte einen kleinen Autounfall und die dritte einen Schuh verloren und alle waren in heller Aufregung. Da blieb mir als Regisseurin manchmal auch nichts anderes übrig, als zu improvisieren. Hinzu kam, dass zwei der Darstellerinnen im Iran sehr bekannte Fernseh-Schauspielerinnen sind, andere sind noch weitgehend unbekannt. Da kamen auch Neid und Konkurrenz ins Spiel. Aber nach einem Jahr der Zusammenarbeit würde ich uns heute alle als Freundinnen bezeichnen.

Frage: Haben Sie als Ausländerin eine andere Sichtweise auf die iranische Gesellschaft als die Einheimischen?

Ich habe natürlich versucht, nicht in die Vorurteilsfalle zu tappen. So hatte ich auch Bedenken, die Darstellerinnen in Zelte schlüpfen zu lassen. Ich dachte, sie würden mir Klischeedenken von wegen armer, unterdrückter Frauen im Iran vorwerfen. Sie selbst stört das nämlich gar nicht so sehr, es ist normal, sie sind so aufgewachsen. Die Leute wollen auch nicht ständig politisieren, man arrangiert sich eben mit dem System. Darin entwickelt die Bevölkerung einen extrem großen Erfindungsreichtum. Allerdings eröffnete sich für die meisten erst mit dem Internet der Zugang zur Welt, die iranischen Web-Logs explodieren geradezu. Die jungen Leute sind schon unzufriedener.

Frage: Apropos Klischees: Haben Sie sich selbst bei vorgefassten Meinungen erwischt?

Durch die Arbeit mit den Darstellerinnen von „Letters from Tentland“ habe ich Einblick in eine Welt bekommen, die in Europa durch Medien und Klischees mehr verstellt worden ist, als dass sie Kenntnisse über das Leben in dieser Gesellschaft vermittelt hätten. Ich wollte beispielsweise eine Terroristenszene à la „Kill Bill“ in das Stück einbauen. Da haben die Performerinnen interveniert, so einen Selbstmordattentäterquatsch wollten sie nicht, da würde die Realität verzerrt, nicht jede Iranerin liefe mit einer Bombe unter dem Tschador herum. Da merkt man dann, dass man fast automatisch auf die einseitigen Bilder aus dem TV zurückgreift. Ich habe zudem viel über Gastfreundschaft gelernt.

Frage: Das Stück hatte in Teheran Premiere und wurde vorab in Deutschland aufgeführt. Wie war die Reaktion des Publikums?

Im Iran ist diese Art des Theaters mit verschiedenen Medien – Videoprojektionen, Geräusche, Text und Tanz – etwas Neues und daher für die Zuschauer allein schon deswegen interessant. Die Bilder, die im Iran jeder mühelos interpretieren konnte, haben sich für Europa aber als zu ‚persisch‘, das heißt, zu indirekt erwiesen. Da die meisten hier wenig über den Iran wissen, wurde der Wunsch nach mehr konkreter Information geäußert. Es gibt keine Vorstellung von den Schwierigkeiten, mit denen das Theater in Iran konfrontiert ist. Und wie stark die Arbeit davon beeinflusst wird, wie wichtig es ist, Bilder zu finden für das, was nicht direkt ausgesprochen werden kann. Am Ende des Stücks haben wir die Frauen aus dem Publikum hinter den Vorhang auf die Bühne eingeladen, was jeweils regen Anklang fand. Wir haben auf Kissen am Boden gesessen und Tee getrunken und dabei den kulturellen Austausch fortgesetzt – sozusagen ein P.S. wie es manchmal am Ende eines Briefes steht.

Politik-Forum |2006

Interview mit Helena Waldmann von Christoph Quarch

Die Sprache des Körpers ist universell- Tanzen ist politisch. Denn wo getanzt wird, kommen Menschen miteinander in Berührung>

Ein Gespräch mit der Choreografin Helena Waldmann

publik-forum: Seit Sie in Ihrer Choreografie »Letters from Tentland« iranische Frauen auf der Bühne haben tanzen lassen, stehen Sie im Ruf, dem zeitgenössischen Tanztheater eine politische Dimension verliehen zu haben. Sind Sie eine politische Choreografin?

Helena Waldmann: Viele meiner choreografischen Arbeiten eine politische Farbe. Das ist aber gar nicht unbedingt gewollt, sondern hat oft einfach mit ihrer Entstehungsgeschichte zu tun. „Letters from Tentland“ ist im Iran entstanden. Die Schauspielerinnen, mit denen ich dort einen Workshop gemacht habe, hatten mich ausdrücklich gebeten, keine politischen Inhalte mit ihnen zu arbeiten. Sie sagten, sie seien es leid mit Europäern immer Politik treiben zu müssen – dass sie einfach nur leben, lieben und lachen wollen. Mir leuchtete das ein, und ich habe versucht, ihre Bitte zu erfüllen. Aber kaum, dass wir zu improvisieren begannen, kam die Politik ins Spiel. Wie sollte es anders sein? Wenn man in einem Land wie dem Iran lebt, ist es nicht möglich, einfach nur zu lachen, zu lieben und zu leben. Jede Äußerung spricht von der Unterdrückung der Menschen.

publik-forum: Dass im Iran der Tanz schnell politisch wird, leuchtet ein. Aber gilt das auch für unsere Breiten? Daher ei ne allgemeinere Frage: Was verleiht einer Choreografie einen politischen Anstrich?

Waldmann: Entscheidend ist die Themenauswahl: das, was im Tanz besprochen werden soll. Vor Kurzem habe ich in Saarbrücken eine Choreografie mit dem Titel »Crash« auf die Bühne gebracht, bei der es um das Thema Migration ging. Die Art und Weise, wie hier getanzt wurde, machte etwas deutlich von der extremen körperlichen Brutalität, die Menschen erfahren, wenn sie an Grenzen abgewiesen werden. Dies mit dem Körper auszudrücken, verleiht einem Tanz politische Wucht.

publik-forum: Lassen sich in der Sprache des Tanzes Dinge sagen, die man in der gesprochenen Sprache nicht ausdrücken könnte?

Waldmann: Ja, wobei ich hinzufügen muss, dass es manch mal auch schwieriger ist, im Tanz etwas auszudrücken. Wir Menschen sind es nun einmal gewohnt, die Welt über Worte zu verstehen. Deshalb führt der direkte Weg über die Sprache zum Kopf. Aber die emotionale Seite der Dinge können Sie so nicht erschließen. Sie lässt sich besser über den Körper vermitteln. Das war in Crash der Fall, wenn Menschen gleichsam an Zäunen kleben bleiben; oder in „Letters from Tentland“ durch das stark emotionale Bild, dass Frauen in Zelten gefangen sind und nicht aus ihnen herauskommen.

publik-forum: Erzählen Sie doch etwas mehr von dieser Choreografie! Was hat es mit „Letters from Tentland“ auf sich? Sie waren die erste Europäerin, die auf die Idee gekommen ist, mit iranischen Frauen eine Choreografie einzustudieren.

Waldmann: Das hat den einfachen Grund, dass es Frauen im Iran verboten ist, in der Öffentlichkeit zu tanzen. Insofern war es einigermaßen absurd, mich dazu einzuladen, dort eine Choreografie einzustudieren. Aber mich reizte die Sache, und so habe ich mich darauf eingelassen. Als wir in Teheran das Stück entwickelten, war der heutige Präsident Ahmadinedschad noch nicht an der Macht. So konnten wir etwas bewegen und »das Wunder von Tschadorestan« vollbringen, wie »Die Zeit« es genannt hat. Tat sächlich konnten wir in Teheran zwei Vorstellungen realisieren. Danach waren wir noch drei Monate auf Tournee.

publik-forum: Was passiert in dem Stück?

Waldmann: Sechs Frauen bewegen sich in Zelten. Das war ein Trick, denn es ist im Iran zwar untersagt, dass Frauen in der Öffentlichkeit tanzen. Es ist aber nicht untersagt, dass Zelte, in denen Frauen sind, in der Öffentlichkeit tanzen. Und genau das geschieht auf der Bühne: Zelte tanzen. Das hatte aber gleichwohl eine provokante politische Komponente, die mir allerdings erst später bewusst wurde: Das Wort Tschador bedeutet sowohl Kleid als auch Zelt. Und so ging das iranische Publikum davon aus, dass die Zelte ein Symbol für den Tschador sind, den Frauen in der Öffentlichkeit tragen müssen. Dabei ging es mir ursprünglich gar nicht darum. Mich hatten vielmehr die vielen Zelte am Stadtrand von Teheran inspiriert, in denen Menschen leben, die vom Land in die Stadt gekommen sind.

publik-forum: Und welches Thema wollten Sie damit transportieren?

Waldmann: Mir ging es um das Thema Öffentlichkeit und Intimität. Es gibt im Iran zwei Leben. Das eine ist innen, das andere ist außen. Man braucht das, um in diesem Land nicht wahnsinnig zu werden. Die Menschen brauchen Rückzugsorte, um ein Gegengewicht zu der Verlogenheit des öffentlichen Lebens zu finden. In der Öffentlichkeit darf man nichts sagen, nichts zeigen: Jedes offene Wort ist gefährlich. Aber daneben gibt es das andere Leben, das wahre Leben, bei dem man sein Gesicht zeigen darf. Dieses Leben spielt sich undercover ab: in den Häusern, in den Wohnungen, in den Hinterzimmern. Dieses innere Leben ist wahr. Das ist es, was die Tänzerinnen zum Aus druck bringen wollten.

publik-forum: Das innere Leben hinter der Hülle des Zeltes?

Waldmann: Genau. Das eigentliche Leben ist verhüllt. Und ich habe im Iran erlebt, dass dieses Leben viel extremer und teilweise auch lustiger und munterer ist als bei uns. Wenn ich privat eingeladen wurde, habe ich dort eine große Lebendigkeit und Lebensfreude erlebt: berstende, bebende Körper, Tanz und Spaß ohne Ende. Hier finde ich das fast gar nicht.

publik-forum: Sie haben „Letters from Tentland“ überall auf der Welt aufgeführt. Eines Tages hieß das Stück dann »return to sender«. Was war passiert?

Waldmann: Nach einem Jahr und drei Monaten erreichte uns ein wirklicher Brief aus dem »Zeltland«, also: aus Teheran. Unsere iranischen Tänzerinnen baten uns, das Stück aufzugeben. Mit der Wahl von Ahmadinedschad hatten sich die Verhältnisse im Iran geändert, und unsere Frauen dort fühlten sich bedroht. Ich wollte sie einerseits nicht gefährden, mir andererseits aber auch nicht vom Iran diktieren lassen, welche Stücke ich zeigen darf. Deshalb habe ich in Berlin lebende Iranerinnen gecastet und sie gefragt, ob es für sie interessant wäre, dieses Stück gleichsam zu überschreiben. So entstand »return to sender«.

publik-forum: Was war daran neu?

Waldmann: Durch die ganz andere Situation der Exil-Iranerinnen veränderte sich die Symbolik: Die Zelte wurden nun zu Bildern für die ungewisse Situation dieser Frauen, die immer auf dem Sprung sind und mit einer Abschiebung rechnen müssen. Aber auch das Verhüllungsmotiv war für die Frauen wichtig. Ich habe begriffen, dass sie sich nach Verhüllung sehnten, um nicht immer gleich als Ausländerinnen wahrgenommen zu werden. Und so haben die Iranerinnen, die in Deutschland leben, ihre »Briefe an den Absender« geschrieben und darin ihren Schwestern in Teheran ihre Exil-Situation dargestellt.

publik-forum: Verblüffend ist, dass diese unterschiedlichen Lebenssituationen mit der gleichen Bildsprache zum Ausdruck gebracht werden können – und dass diese Sprache von Menschen überall auf der Welt verstanden wird. Ist Tanzen so etwas wie eine universale Sprache?

Waldmann: Absolut ja. Die Körpersprache gibt es überall und jederzeit. Und in ihr können sich Menschen mit noch so unterschiedlicher kultureller Herkunft verständigen.

publik-Forum: Aber es gibt doch große Unterschiede: In Japan tanzen die Menschen ganz anders als in Afrika, und die Latinos tanzen anders als die Inder.

Waldmann: Die unterschiedlichen Tanzformen erzähle: etwas von den unterschiedlichen Kulturen, in denen Menschen leben. Und doch kann man entziffern, was sie in ihnen jeweils auf eigene Weise ausspricht. Denn die Körpersprache ist bei allen kulturellen Differenzen an Ende doch eine und dieselbe.

publik-forum: Dann wäre der Tanz ja ein wunderbares Verständigungsmittel in der globalisierten Welt.

Waldmann: So ist es. Und wissen Sie: Ich bin davon überzeugt, dass der Tanz ein Medium ist, in dem Kulturen und Religionen miteinander kommunizieren können – eint Sprache, in der sich Muslime und Christen, Juden und Buddhisten verständigen können.

publik-forum: Was sie aber selten tun. Warum?

Waldmann: Weil wir – gerade in Deutschland – den Sinn dafür verloren haben, uns im Tanz auszudrücken. Die Menschen tanzen kaum noch. Sie schauen sich vielleicht Tanz-Filme im Kino oder Tanz-Performances in Theater und Oper an, aber sie haben den Bezug zu ihrem eigenen Körper verloren und dessen Sprache verlernt. Es wäre gut, wenn die Menschen hierzulande wieder entdecken würden, was es bedeutet, auch mal den Kopf zu verlieren.

publik-forum: Wie wollen Sie das unseren Zeitgenossen beibringen?

Waldmann: Die Menschen müssten wieder lernen, Verantwortung zu übernehmen und aktiv zu werden: nicht vorn Fernseher oder im Zuschauerraum sitzen und tanzen lassen, spielen lassen, kochen lassen. Was wäre das für eine Alternative zu sagen: Wir machen das jetzt selbst!

publik-forum: Aber die Leute tanzen doch. Tango steht hoch im Kurs, bei der Love-Parade raven Hunderttausende. Es ist nicht so, dass die Leute in Deutschland nicht tanzen würden.

Waldmann: Das stimmt, aber am Ende ist es nach meinem Eindruck doch eine Minderheit, die tanzt. Und selbst dann fehlt oft der Sinn dafür, dass Tanz Kommunikation ist. Damit will ich nicht sagen, dass nur der Paartanz ein richtiger Tanz wäre. Man kann auch auf andere Weise tanzend mit dem Körper kommunizieren. Entscheidend ist, dass Sie beim Tanz das Interesse haben, mit einem anderen Menschen »ins Gespräch« zu kommen. Und das fehlt mir in diesem Land. Die Menschen schauen sich kaum in die Augen, sie machen immer mehr zu. Wie soll man da er warten, dass sie miteinander tanzen? Sie tun es nicht.

publik-forum: Womit wir wieder bei den Zelten wären.

Waldmann: Genau. Aber jetzt kommt das Entscheidende: In den Zelten, hinter den Verhüllungen, rumort und pulsiert es. Da regt sich ein Schrei nach Freiheit. Da rührt sich eine herumirrende Seele, die wild tanzt und wirbelt. In „Letters from Tentland“ drehte sich eine Frau in ihrem Zelt wie ein Derwisch. Das war ihre Art, Gott anzurufen. In solchen Momenten wird der Tanz zu einer hochspirituellen Angelegenheit. Ich weiß nicht, ob die Zuschauer in Deutschland das wahrgenommen haben, aber im Iran und in anderen islamischen Ländern war den Leuten klar, dass sie einem spirituellen Tanz beiwohnten.

publik-forum: Haben Ihre Tänzerinnen das auch so gesehen?

Waldmann: Sie haben immer wieder betont, dass sie ein intensives Verhältnis zu Gott haben und das auch zum Aus druck bringen wollen. Allerdings nicht in den ritualisierten Formen von Niederwerfung und dergleichen. Sie haben Gott mit ihrem individuellen, improvisierten Tanz angerufen. Ich fand das sehr schön.

publik-forum: Tanzen – das spirituelle Gegengift in einer kommunikationsarmen Welt. Steht diese These im Hintergrund Ihrer neuen Choreografie »feierabend! – das gegengift «?

Waldmann: Nicht das Gegengift, aber ein mögliches bestimmt. Tanzen bedeutet für mich immer auch Feiern: Und auch Feiern ist etwas, das wir hierzulande wieder entdecken müssen. Die Menschen in Deutschland sind total auf Arbeit fixiert – und wissen mit ihrem Feier-Abend oft nichts mehr anzufangen. Diesem Thema gilt meine neueste Choreografie. Sie handelt vom Feiern als Gegengewicht zur Arbeit. Zu einer guten Feier gehört aber immer der Tanz. Weil der Tanz ein Mittel ist, das es erlaubt, einfach mal den Kopf abzuschalten. Der Kopf ist der Eintrittspreis. Wenn Sie zum Fest des Lebens wollen, dann kostet Sie das den Kopf – oder wenigstens den Verstand.

Press

english

Dance Europe | Dec 2004

by Katja Werner

Katja Werner contemplates Helena Waldmann's take on Islamic culture>

An official censor is present at the performance at Munich’s Theater im Haus der Kunst. Nothing will be shown that he has not condoned. On the other hand, hardly anything is shown.

Katja Werner contemplates Helena Waldmann’s take on Islamic culture

“Letters from Tentland” is the fruit of an unusual co-operation across cultures that are said to be incompatible. Ten to one, its German audience’s image of post-Shah Iran stems largely from Betty Mahmoody. Women with no rights, no voice, hidden, helpless, and enslaved. Prisoners, in short, if they are lucky. Such are the tales we like to listen to. That’s very charitable of us. But how about some first-hand information before we sign another petition on behalf of the Unknown Oppressed?

Helena Waldmann travelled to Teheran for five weeks to work with a group of Iranian women – actresses and dancers – and the workshop developed into something of a piece, so they decided to tour it. Festivals in Hannover and Munich offered rehearsal space, and both witnessed pre-premiere try-outs. In the process the production’s name had to be changed, “Teheran” was replaced by “Tentland”. There could be more alterations before the final version will be presented at a theatre festival in the Iranian capital. An official censor is present at the performance at Munich’s Theater im Haus der Kunst. Nothing will be shown that he has not condoned. On the other hand, hardly anything IS shown. While we know from the programme that Zoreh Aghalou, Pantea Bahram, Mahshad Mokhberi, Banafsheh Nejati, Sara Reyhani, and SimaTirandaz will be performing, all we see is a row of small tents in different colors on a white dance floor.